- © 2025 The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Incorporated

- Terms of Use

- Site Map

On December 21, 1978, the Corporation becomes responsible for the management, maintenance and monitoring of the Jacques Cartier Bridge.

In June 2023, JCCBI has started surveying the area near the Île Sainte-Hélène Pavilion (ISHP) to explore its archaeological potential before excavation work is done.

A highlight in fall 2022 was the project to develop land under the Jacques Cartier Bridge. As part of its role as a social and urban contributor, JCCBI redeveloped this sector into an enjoyable and informational site for local residents and pedestrians. Each information plinth at the new site was installed on a piece of deck slab taken from the former roadway of the original Champlain Bridge.

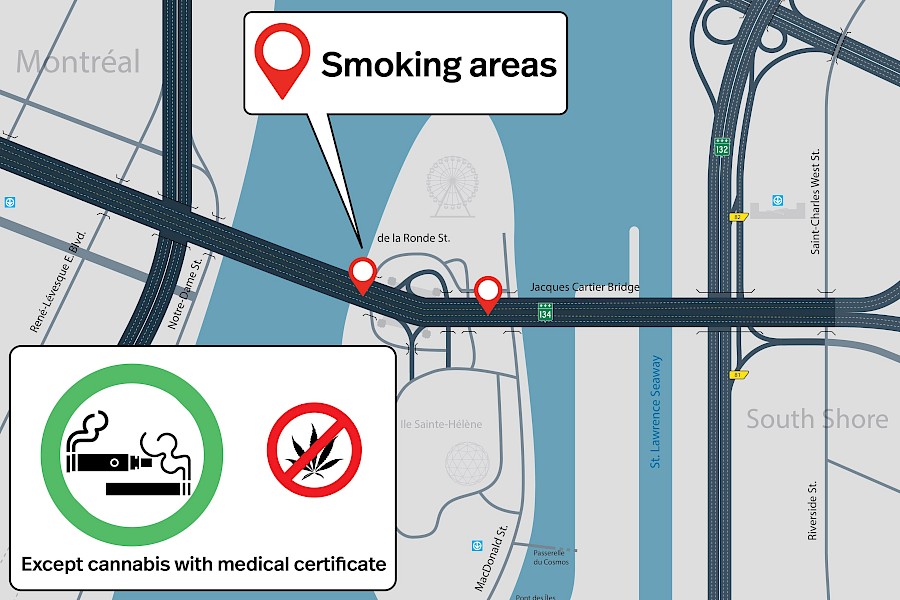

In effect since the summer of 2022, smoking areas aim to provide a smoke-free environment for all spectators during the fireworks at the Jacques Cartier Bridge. Smoking is therefore prohibited on the bridge during these evenings, except in designated areas (see map below). Visit our webpage for all the details and instructions.

In March 2022, anti-glare fencing was installed on the Jacques Cartier Bridge’s multipurpose path to reduce the glare from vehicle headlights at four locations identified by cyclists during discussions with JCCBI.

The XVI World Winter Service and Road Resilience Congress was held in Calgary from February 7 to 11, 2022. After working with our partner Arup on the winter maintenance project for the Jacques Cartier Bridge multipurpose path and sidewalk, our teams were proud to win the PIARC-Québec 2022 National Award.

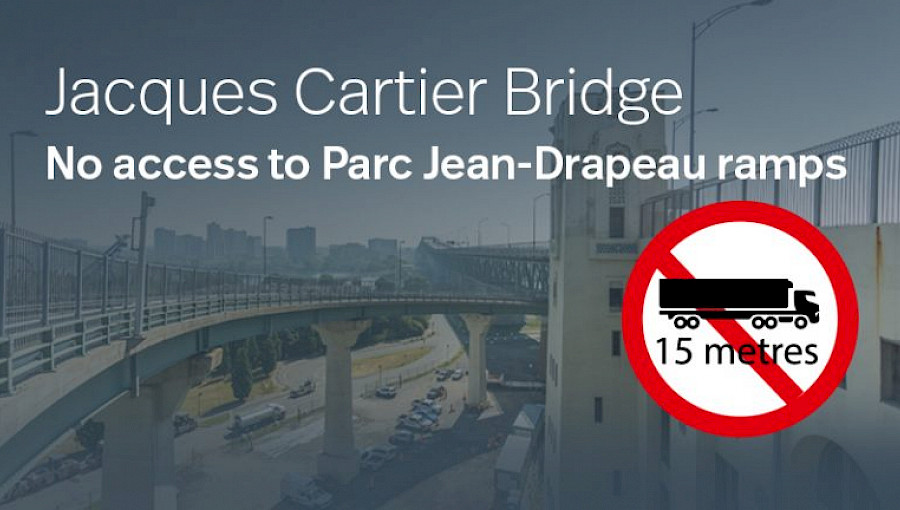

Vehicles over 15 metres (over 50 feet) in length are prohibited from using the access ramps of the Jacques Cartier Bridge leading to Parc Jean-Drapeau.

This preventive measure is in effect on the two entrance and exit ramps between the Jacques Cartier Bridge and Parc Jean-Drapeau. This measure was implemented by JCCBI following instances in which vehicles over 15 metres in length became stuck in a ramp and thus encroached over several traffic lanes thereby posing significant safety risks for bridge users and causing damage to equipment.

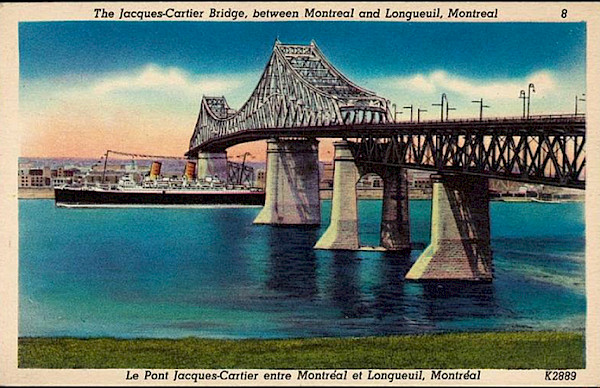

The Corporation was proud to mark the 90th anniversary of the Jacques Cartier Bridge, which has served as an essential corridor between Montreal and the South Shore since May 14, 1930. JCCBI has been managing this iconic structure since 1978 and is taking great care of the bridge to extend its service life until 2080.

JCCBI proposed a look back at nine decades of history, innovation, engineering and mobility!

Government of Canada marked the 90th anniversary of the Jacques Cartier Bridge.

In 2020, Mr. Stephen Hersey informed JCCBI that he wanted to donate the trowel used to inaugurate the Jacques Cartier Bridge, which had been in his family for almost 100 years. The trowel was used by his great-grandfather, Dr. Milton Lewis Hersey, on August 9, 1926, to lay the cornerstone for this exceptional structure.

As part of its work under the Jacques Cartier Bridge, The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Incorporated (JCCBI) conducted an archaeological dig near some bridge piers located south of De Lorimier Avenue. The goal of the dig was to find the location of a kiln used in the 19th century to fire pipes. Today, we are pleased to announce that the researchers located a massive pipe kiln from the Henderson factory.

Photo credit: Carl Ritondo, Atwill-Morin and Dan Simirea, CIMA+ Hatch

As the Henderson pipe factory was founded in 1847 by William Henderson, Sr., and taken over by the founder’s grandsons, the Dixon brothers, in 1876, this kiln may have been built sometime between 1847 and 1892. It is possible that the kiln was rebuilt along the way, as this type of equipment required regular maintenance and repairs.

Photo credit: Simon Filiatrault, Eng. M.B.A., EXP

Old maps of the area confirm that the land lot was occupied by the Hendersons and Dixons starting in 1847. One of the maps illustrates the kiln’s location in the factory’s back yard, and “Henderson / Montreal” is even stamped on most of the pipes found around the kiln and on the land lot discovered directly to the west (near Sainte-Catherine Street) in 2005.

Photo credit: Mr. Christian Roy, archaeologist

Faubourg Sainte-Marie, as it was called at the time, was a working-class neighbourhood with many industries concentrated in the food, textile, leather and tobacco sectors. In the last quarter of the 19th century, glass and metalwork plants were added to the neighbourhood. Faubourg Sainte-Marie, and specifically the quadrangle formed by Sainte-Catherine, De Lorimier, Viger and Dorion, was also known as Montreal’s pipemaker’s district.

According to the manufacturer’s census records, the Henderson factory employed about fifty workers in both 1861 and 1871. From 225 tonnes to 300 tonnes of pipe clay were processed annually and, in 1871, nearly 7 million pipes were produced per year, which equals 22,000 boxes or 50,000 gross (1 gross = 12 dozen). The Hendersons were of Scottish descent and native to Glasgow, and most of their employees were Scottish and Irish immigrants.

JCCBI has completed the archaeological dig in this area where most of the remains have been found.

For Canada’s 150th anniversary and Montreal’s 375th anniversary, JCCBI invites the public to come see the very first illumination show on the Jacques Cartier Bridge. Overall, 400,000 spectators come to admire the bridge in its full colourful glory!

The interactive Living Connections installation was spearheaded by JCCBI and developed by a team of local creators.

Thanks to intelligent programming, the Jacques Cartier has become the first “people-connected” bridge that comes alive every night in an animated light sequence that changes with the seasons and the pulse of the city. This innovative installation has become a signature for Montreal and will make it shine for years to come.

Reinforcement and stabilization of the approaches of the Jacques Cartier Bridge in order to extend the service life of this Montreal icon to at least 75 years.

Part of the major repair program of the Jacques Cartier Bridge, this work was done mainly on the bridge’s south approach (east embankment) on the Longueuil side.

An architectural staircase was also built into the east embankment to connect the Jacques Cartier Bridge sidewalk with Saint-Charles Street and thereby enhance pedestrian mobility.

To celebrate Canada’s 150th anniversary and Montreal’s 375th anniversary in 2017, the Government of Canada announces a large-scale interactive light project for the Jacques Cartier Bridge.

Start of program to clean and paint the entire steel structure

Spanning 15 years and covering a surface area of 450,000 m², this is the largest project of its kind in Canada.

Photo. Enclosures installed at the main span for cleaning and painting work (2003)

The Corporation becomes responsible for the management, maintenance and monitoring of the Jacques Cartier Bridge, the Champlain Bridge and a section of Bonaventure Expressway.

Photo. The Jacques Cartier Bridge at the time of construction of the Olympic Basin (1976)

Photo credit: Archives de la Ville de Montréal

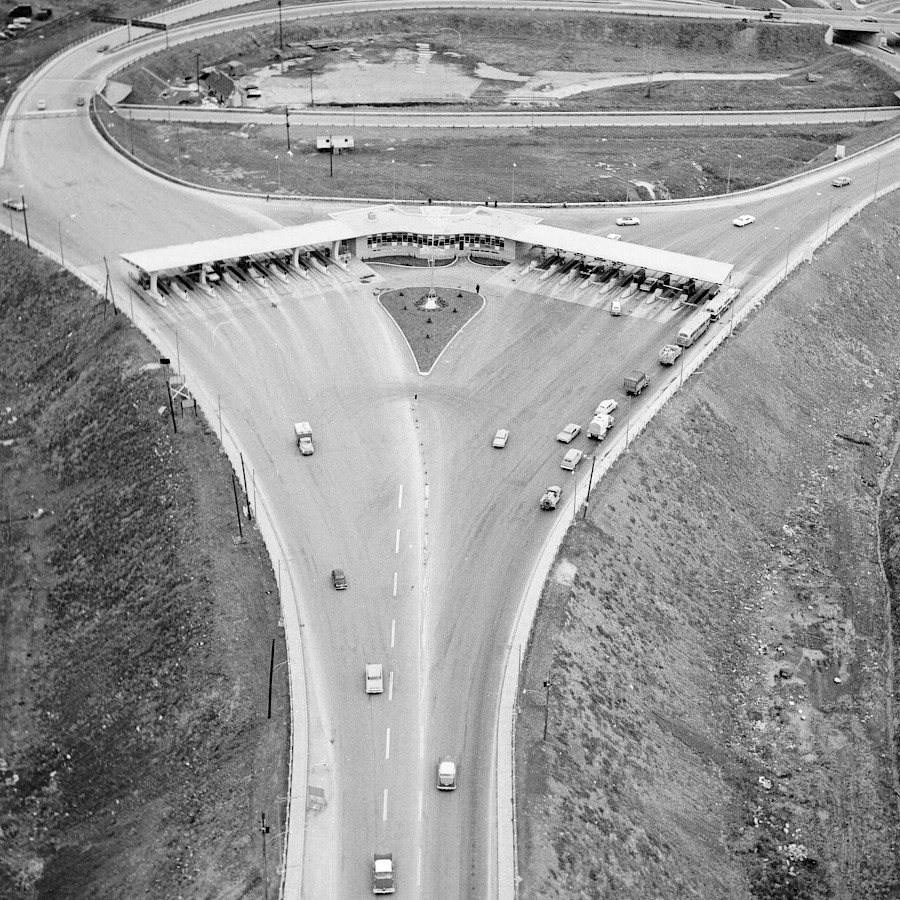

The toll had been in place since the bridge opened in 1930. Since then, the toll collectors’ building has been used as the main office for Jacques Cartier and Champlain bridges maintenance personnel.

Toll collectors were replaced by an automatic toll system in an attempt to improve traffic movement and control of the money.

Opening of a fifth lane

Inauguration of a fourth lane.

Photo. Inauguration of the fourth lane with Jean Drapeau, major of Montréal (1956)

The bridge received its new official name, and the bronze bust was unveiled. The bust was presented by Mr. Henry Bordeaux and was accepted on behalf of Canada by the Minister of Marine at the time, the Honourable Alfred Duranleau.

The resolution recommending that the Harbour Bridge be renamed the “Jacques Cartier Bridge” was approved by a ministerial decree. On this date, the government of France gave Canada a bronze bust of the famous explorer and discoverer from Saint-Malo.

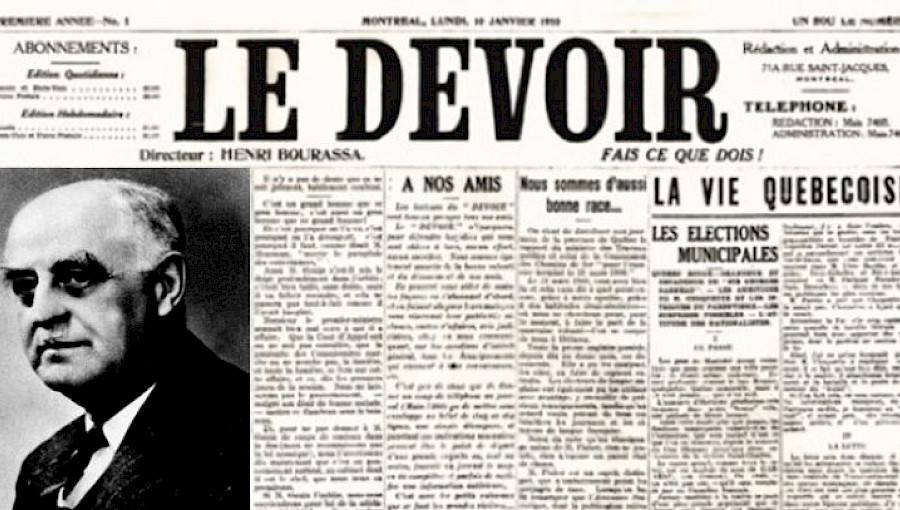

In response to public demand following a petition started by Le Devoir editor Georges Pelletier, the Harbour Commissioners of Montreal adopted a resolution recommending to His Excellency the Governor General in Council that the Harbour Bridge be renamed the “Jacques Cartier Bridge” in homage to the French explorer and in recognition of the 400th anniversary of his arrival in Canada in 1534.

The inauguration ceremony started with a speech from the chairman of the Harbour Commissioners of Montreal, Senator W. L. McDougald. Monseigneur Georges Gauthier, archbishop of the diocese of Montreal, blessed the bridge. At 11:50 am., the Right Honourable William Lyon Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada, gave his speech by telephone from his office in Ottawa. He then open the curtains to unveil the commemorative plaque. At the time of the inauguration, the bridge was named the “Pont du Havre” or the “Harbour Bridge,” as it was built by the Harbour Commissioners of Montreal.

Photo. William Lyon Mackenzie King

Since its inauguration, users had to pay to cross the Jacques Cartier Bridge and only cash was accepted. Later, it was possible to raise toll fees, valid for the Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges.

Photo. Toll booth

Photo. First operating year of the Jacques Cartier Bridge (1930)

The three-lane bridge is opened to traffic.

At first, the bridge only had three lanes, as a 3.6-m wide lane was built on either side for streetcars, leaving 11.2 m of roadway for vehicles. As the downstream lane was never used for streetcars, it was opened as a fourth lane to traffic on June 1956. In 1959, a fifth lane was open and used in either one direction depending on traffic.

A cornerstone was laid into Pier 26 at the corner of Notre-Dame Street and Craig Street (now Saint-Antoine Street) across from a spot called “the foot of the current” (“Au Pied du Courant”). No one knows the exact location of the stone on the pier, but we do know it contains a time capsule with 59 objects.

Photo credit: Archives de la Ville de Montréal

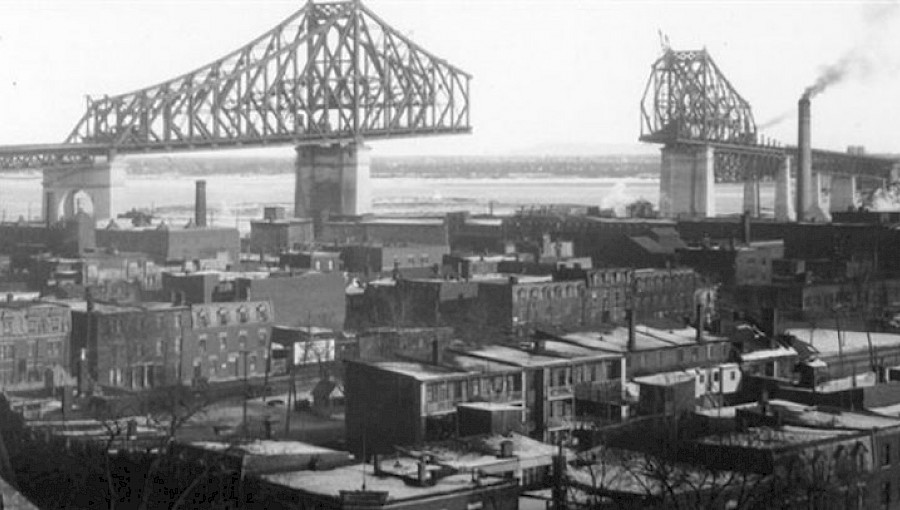

Ground breaking ceremony

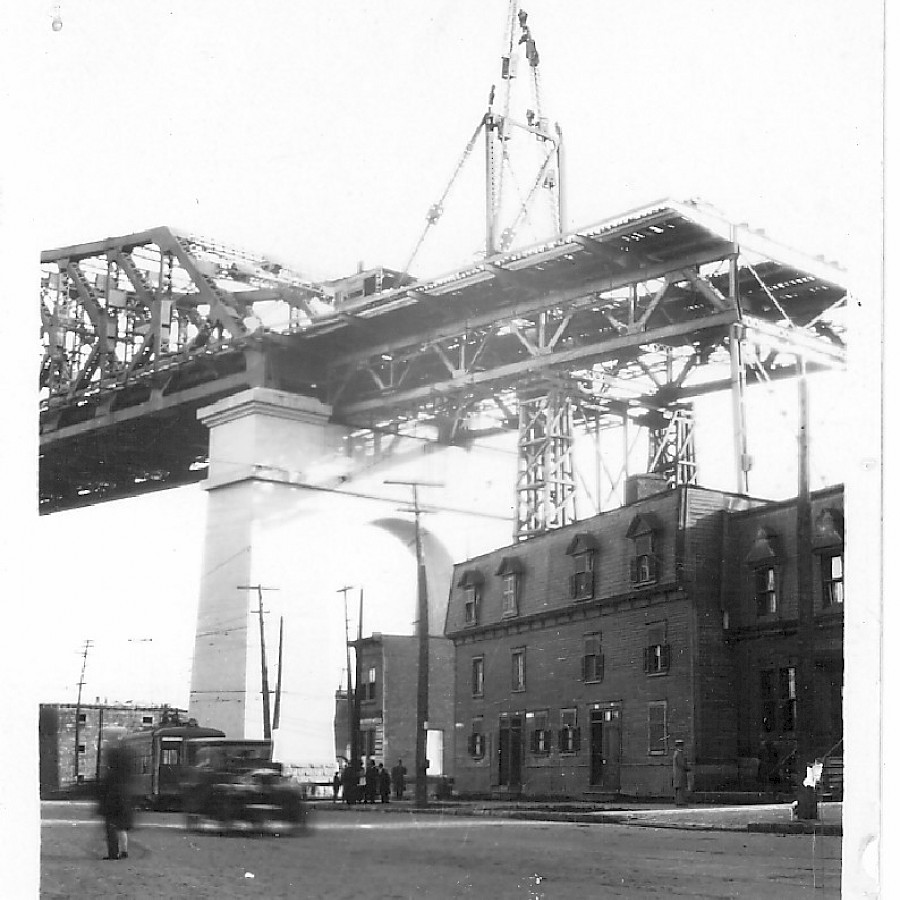

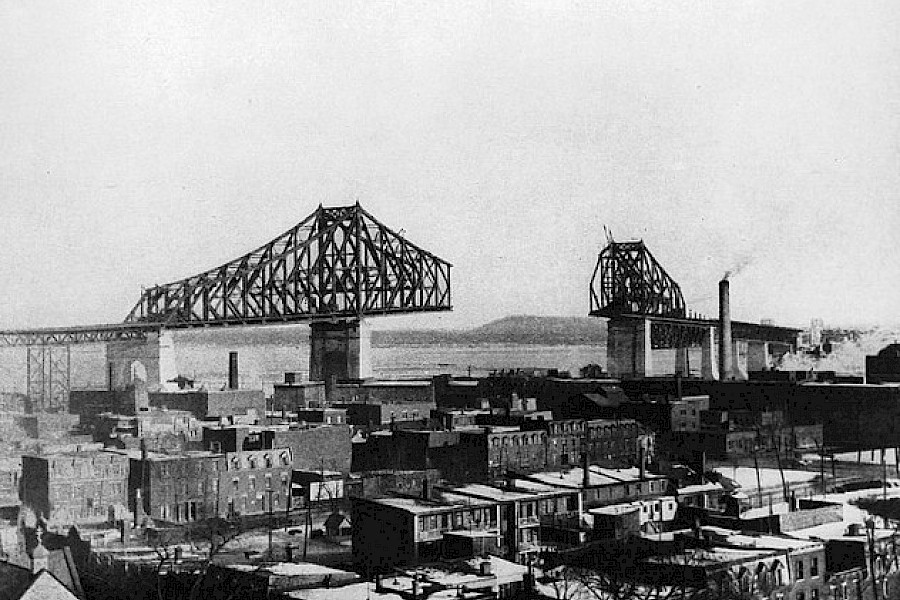

Started in 1925, the bridge construction took four years. The work was done so quickly that the contractors delivered the bridge in December 1929 instead of May 1931, or nearly a year and a half earlier than expected.

The construction cost was approximately $23 million (1929), including expropriation expenses and the approaches on the fill sections.

Photo. Construction of the Jacques Cartier Bridge (1929)

Photo. Construction of the Jacques Cartier Bridge (1929)

The bridge site is chosen.

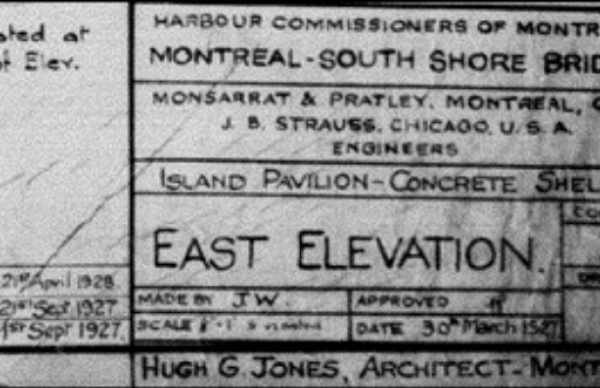

A competition is launched for the bridge site. The Harbour Commissioners of Montreal announce that they have selected the Monsarrat and Pratley of Montreal engineering firms for the project.

Citizen committees, the Board of Trade, the Montreal Chamber of Commerce, the Civic Improvement League, and several other organizations submitted a report to the Honourable P. J. A. Cardin, Minister of Marine and Fisheries, about the need for a new link between the South Shore and Montreal.

From Longueuil, people could take two ferries to Montreal during the summer. During the winter, motorists could risk crossing an ice bridge during the few weeks of severe cold. The need for a new link between Montreal and the South Shore was becoming more and more urgent.

In your travels over the Jacques Cartier Bridge, you’ve probably noticed one of the four turrets on the roof of the Île Sainte-Hélène pavilion found half-way between Montreal and the South Shore. Built between 1927 and 1931, this Art Deco building, a rare style in Montreal, is, of course, located on Île Sainte-Hélène. With a total area of 7,145 square metres, the pavilion has two basements, a ground floor, an upper floor and a mezzanine. Its foundations were built into the side of the bedrock. The building is made of concrete slabs and walls and a system of steel beams and columns. Interestingly, the pavilion roof forms the Section 5 deck of the Jacques Cartier Bridge.

A pedestrian walkway was built into the pavilion to connect the east side (sidewalk) and west side (multipurpose path) of the Jacques Cartier Bridge. In this tunnel, two murals by Montreal artist Rafael Sottolichio take users on a journey back in time and show images of the city when it was humming to the sound of massive development projects. This tunnel is also a point of interest in the Stories and Bridges technical and historical tour.

Originally the pavilion was supposed to be a casino, but this project never got off the ground because the church vetoed the idea. The next plan was to create ballrooms and exhibit halls, but these were never completed either.

As time went on, the Second World War and the economic crisis of 1929 gave the pavilion an unexpected purpose, as the Canadian army took over the building to use as a warehouse, which it did until the start of the 1950s. On the initial engineering plans, the Jacques Cartier Bridge was to have three traffic lanes and a reserved streetcar lane on each side. The Île Sainte-Hélène pavilion was therefore going to be a streetcar station. But since no streetcar ever made it over over the Jacques Cartier Bridge, this was yet another plan that never came to pass !

Giving the pavilion a new purpose

Today the pavilion primarily serves as a bridge pier, and The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Incorporated (JCCBI) has done multiple repairs to its infrastructure: painting the building, reinforcing the steel columns, cleaning and painting existing steel components, and reconstructing the girder-slab on the ground floor as well as the basement slab. All of this work has been an investment in the future to ensure, among other things, that the pavilion lasts as a support structure for the Jacques Cartier Bridge. Part of the Montreal landscape for over 85 years, the Île Sainte-Hélène pavilion has stood strong throughout the decades. The Corporation is proud to help preserve this heritage building and has started a process on how to redevelop and enhance this one-of-a-kind structure.

A lawyer and politician at the provincial and federal levels, Alfred Duranleau did his graduate studies in Montreal at Université Laval (which become Université de Montréal in 1920) before being called to the Barreau du Québec. He was the Minister of Marine and Fisheries when the Harbour Bridge was renamed the Jacques Cartier Bridge. During the official naming ceremony, the Honourable Alfred Duranleau received the gift of a bronze bust from the French Government on behalf of Canada.

What do we know about Alfred Duranleau?

A native of Farnham, he studied the law and worked as a lawyer in Montreal before embarking on a career in politics in 1923. He served as an MNA in the provincial riding of Montréal-Laurier and an MP in the federal riding of Chambly-Verchères before being appointed as a federal minister. On September 1, 1934, Mr. Duranleau officially proclaimed the Harbour Bridge’s new name in the presence of a special delegation from France. This highly formal ceremony was held right on the bridge amidst the sounds of the Canadian and French national anthems being played by a brass band.

Alfred Duranleau was also involved in the local community and active with organizations such as the examination board of the Barreau du Québec, Hôpital Notre-Dame in Montreal, the Montreal chamber of commerce, and the Montreal press club.

A key figure of Montreal history, Camillien Houde had a career in politics for many years and served as mayor of Montreal on and off between 1928 and 1954 . Nicknamed “Mr. Montreal,” he attended the inauguration of the Jacques Cartier Bridge on May 24, 1930.

Did you know that Camilien Houde was a prisoner at the internment camp in Petawawa, Ontario?

After getting a degree in commerce, Houde began his career in banking and then worked as a representative of the J. Dufresne de Joliette cookie company. He quickly developed a strong interest in politics and became a member of the provincial conservative party.

Camillien Houde won a seat in the National Assembly for the first time in 1923 in the riding of Sainte-Marie. From the working-class neighbourhood of Saint-Henri, he ran and was elected mayor of Montreal on a promise of opening up city hall to help ordinary citizens. Early in his first term, the misery caused by the Great Depression guided his mandate. His administration gave $100,000 to the Société de Saint-Vincent de Paul to help the poor and launched large-scale projects such as the construction of viaducts, the Botanical Garden, and the Mount Royal and Parc LaFontaine chalets. Truly engaged with his local Montreal constituents, Houde transformed his Saint-Hubert home into a place for support and assistance.

As the Second World War unfolded, Houde openly declared his opposition to any form of conscription to a number of journalists. His public declaration drew the ire of the government, and he was arrested by the mounties. He was detained at the Petawawa internment camp for four years. In 1944, a jubilant Montreal crowd at the Windsor Station welcomed Houde back home, and they re-elected him that fall.

The great lifetime honours he received include being named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire and a Knight of the French Légion d’honneur. He was known for his flamboyant style, his sense of humour, and his penchant for black Tueros cigars.

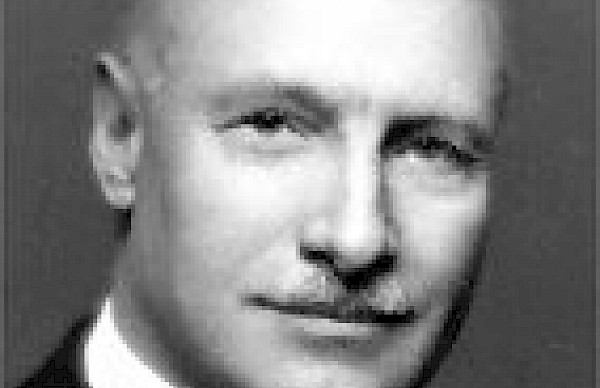

As editor-in-chief of Le Devoir, Georges Pelletier launched a petition to get the Harbour Commissioners of Montreal to rename the Harbour Bridge the “Jacques Cartier Bridge.” His mission was a success, as the bridge has borne the name of this French explorer and discoverer since June 1934.

What do you know about Georges Pelletier?

After getting his bachelor of arts and a law degree, Georges Pelletier started his career as a lawyer in Rivière-du-Loup, where he also wrote for the local newspaper. Journalism started taking more and more of his time, and he gave up his legal practice in 1908 to become a journalist for L’Action catholique. Over the next two years, Georges Pelletier worked as a reporter and political correspondent in Ottawa.

When Le Devoir was launched in 1910, Georges Pelletier joined the newspaper first as a parliamentary correspondent in Ottawa and then as an editorial assistant in Montreal. In 1932, he became the publication’s editor-in-chief. During his tenure, he created key relationships with political leaders such as Canadian Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, all while covering the First World War and denouncing Canada’s participation in this conflict. Pelletier also helped straighten out the newspaper’s finances.

Photo credit: Archives Le Devoir

His career took an unexpected turn when he collapsed while waiting for a train in Edmonton, after which he could no longer use a typewriter.

When Georges Pelletier had another health relapse in August 1946, the newspaper’s board of directors temporarily relieved him of his duties and gave Archbishop Joseph Charbonneau the role of first-named trustee so that the management of Le Devoir wouldn’t fall into the hands of politicians or financial groups. Georges Pelletier died in January 1947.

When technological progress started knocking on the doors of cities at the start of the 1920s, over 6,000 cars could be found on the streets of Montreal. The demand for easy access back and forth to the South Shore gave rise to the project for the Jacques Cartier Bridge, which involved many engineers from North America.

To make this ambitious project a reality, residents on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River (Ville-Marie today) had to pay a high price. In 1926, a series of expropriations forced many Montrealers to give up their homes and businesses so that the Jacques Cartier Bridge could be built. However, one business-owner named Hector Barsalou flat-out refused to move his soap factory.

Photo credit : Les savons Barsalou

Did you know that we owe the Jacques Cartier Bridge’s Montreal curve to Hector Barsalou?

The son of businessman Joseph Barsalou, Hector took over the reins of his family’s soap factory with his brother. The entrepreneur then developed a new technology that allowed the factory to produce 6,000 pounds of soap in an hour and a half instead of one week. With this increased production, the Barsalou brothers could sell their soap to middle and lower class families instead of to just the affluent.

Since their business was booming, the two brothers declined the purchase offer from the corporation in charge of building the bridge. As a result, the bridge designers had to find another option, and the engineers came up with the idea of curving the bridge as it approached the island, earning it the nickname “the crooked bridge.” As for the soap factory, you can still find it at 1600 De Lorimier Avenue.

Today, our prevailing expropriation laws only allow landlords to refuse government demands and force change to large-scale projects in very rare cases.

Novelist Henry Bordeaux gave Montreal a bronze bust of Jacques Cartier, on behalf of his native land of France, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of this explorer’s discovery of Canada. This gift was made in honour of the official name change of this bridge linking Montreal to the South Shore. Formerly called the Harbour Bridge, it was renamed for the famous French explorer who discovered Canada.

What do we know about Henry Bordeaux?

As the son of a lawyer, Henry Bordeaux continued his family tradition and studied the law as well. After practising for several years, he decided to pursue his passion and began a career as a novelist. Almost all of Bordeaux’s novels are set in his native city of Savoy, and his key themes relate to the family and traditional religious and moral values.

One of Bordeaux’s works recounts his trip to Canada, when he gave the bronze bust to Canada’s Minister of Marine on June 30, 1934. The official ceremony was attended by American and British dignitaries and representatives from Montreal’s business, finance and industry sectors, who came to witness Bordeaux’s symbolic gift from France.

Why change the name?

Although most people called it the “South Shore Bridge” before it was officially named the Harbour Bridge in 1930, a single name never stuck. After Le Devoir Editor-in-Chief Georges Pelletier filed a petition to change the name, the bridge authorities bowed to popular will and named the structure the “Jacques Cartier Bridge” in homage to the renowned explorer.

Architect and artist Hugh G. Jones put his creative talent to work to create both structural drawings and works of art, and some of his pieces can be found on display at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. After training in Minneapolis, Jones worked in Chicago and New York before moving to Montreal. During Montreal’s urban planning and development at the end of the 1920’s, he was involved in the construction of the Île Sainte-Hélène pavilion, which is an annex of the Jacques Cartier Bridge.

What do we know about this mysterious architectural jewel?

Built from 1925 to 1930 at the same time as the Jacques Cartier Bridge, the pavilion was built with two floors that could fit up to 6000 people. Originally designed to hold large social events like exhibits or balls, some people even thought it would be a good place for a museum or a casino.

However, the economic crisis of 1929 changed the pavilion’s fate, as the government ordered a halt to all large-scale projects due to the stock market crash.

The pavilion’s fate was therefore put on permanent hold, and the building never even received an official name. Some called it the Île Sainte-Hélène pavilion, while others referred to it as the Jacques Cartier Bridge pavilion.

Although the building is currently unoccupied, it has great heritage value for Montrealers. JCCBI is currently doing major repairs and is hoping to start upgrades soon so that the pavilion can be put to a long-term use.

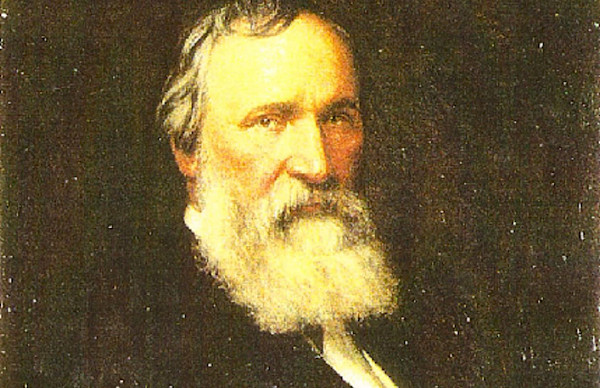

An influential member of the Harbour Commissioner’s of Montreal (the predecessor of the Montreal Port Authority), John Young was one of the first people to lobby for a bridge that connected the Island of Montreal to the South Shore. To encourage economic trade, this businessman called for the construction of what would be called the Royal Albert Bridge at the location where the Harbour Commissioners later inaugurated the Jacques Cartier Bridge in 1930.

Did you know that John Young is considered the father of the Port of Montreal?

A native of Scotland, John Young immigrated to Ontario at the age of 15 and moved to Montreal four years later. With the goal of turning Montreal into a true business centre, he also started supporting the construction of many rail lines in the 1840’s , and in 1845 he called for the construction of the Victoria Bridge.

Photo. Portrait of John Young

Photo credit: Unknown source

Some of the biggest projects of John Young’s career were with the Harbour Commissioners of Montreal. As its chairman from 1853 to 1866, he helped develop the Port of Montreal, particularly when it came to organizing customs, installing sea buoys, building docks, and training staff.

A legacy for Montrealers

Ambitious and anxious to see the city prosper, Young was one of Montreal’s most well-known public figures from the last half of the 19th century. Today, a bronze statue of Young stands in the Old Port of Montreal, at the corner of Commune and d’Youville, in front of the seaway where dozens of ships used to pass.

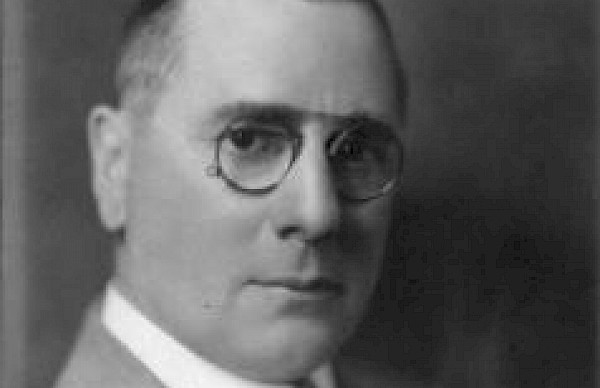

Joseph Baermann Strauss dreamed of having a career in the arts and playing for his university football team. He ended up becoming a prolific engineer known for revolutionizing the design of bascule bridges. Over his career, he helped build over 400 drawbridges across North America, and he is most known for the famous Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco and the Jacques Cartier Bridge, an iconic symbol of Canadian architecture.

Photo credit : San Francisco Public Library

Did you know that the St. Lawrence once had an ice bridge?

In 1921, two ferries and an ice bridge (in addition to the Victoria Bridge) let people go back and forth between Montreal and the South Shore year-round. When these methods could no longer meet demand, the Montreal Chamber of Commerce and other non-governmental organizations joined forces to lobby for another bridge. With his partners Philip Louis Pratley and Charles Monsarrat, Strauss worked on the plans for the Jacques Cartier Bridge from 1925 to 1930.

Have you ever noticed the Jacques Cartier Bridge’s particular shape?

Interestingly, the new bridge ended up having three curves, one of which was not included in the engineers’ original designs.

The first curve over Île Sainte-Hélène was designed to protect the piers from the St. Lawrence River’s turbulent currents. The second curve, which is to the west of the cantilever span, aligns the bridge with Montreal’s north-south avenues. The third and last curve was not part of the original plans and was added near the western abutment because the owner of a soap factory refused to sell his property to the bridge’s management corporation.

Engineer, surveyor and architect Marius Dufresne did his graduate studies at the École Polytechnique de Montréal before starting his career at the Longue-Pointe railway workshop. An expert in the construction of tunnels, bridges, dams and power stations in Quebec, he also helped build the Jacques Cartier Bridge substructure.

Photo credit: Digital Museums Canada, Community Stories

Did you know that Marius Dufresne designed the plans for his own château-style mansion?

From 1908 to 1918, Marius Dufresne worked as a civil engineer for the Cité de Maisonneuve. During this time, he actively participated in many of the city’s urban design and beautification projects that now form part of the architectural heritage of the Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve borough in Montreal. These landmarks include the Maisonneuve Market, the firehall, Maisonneuve City Hall as well as the Morgan public bath. A few years later in 1926, Marius Dufresne was involved in the construction of the Jacques Cartier Bridge, as he helped build the north piers and the structure’s deck. When the work began, the workers had to dig down to the bedrock at the gigantic work site to stabilize the piers. At the north and south approaches, the piers were built with steel and concrete, and their construction would require the use of 4,000,000 rivets, 475,000 bags of cement, and 33,000 tonnes of metal.

In his free time, the engineer designed the plans for his home, the Château Dufresne, which he built with the help of his brother Oscar and the French architect Jules Renard. Built as a double residence, Dufresne’s home was designed in the “château style” of Beaux Arts architecture, which was admired by the French-Canadian bourgeoisie at the time for its elegance.

Photo credit: Stéphane Tessier

The Dufresne family lived there until 1940, when it was sold to the Pères de Sainte-Croix as a boarding school for children in the area. After being left vacant and subsequently restored by the MacDonald Stewart Foundation, the Château Dufresne was converted into the Dufresne-Nincheri Museum that stands at the site today.

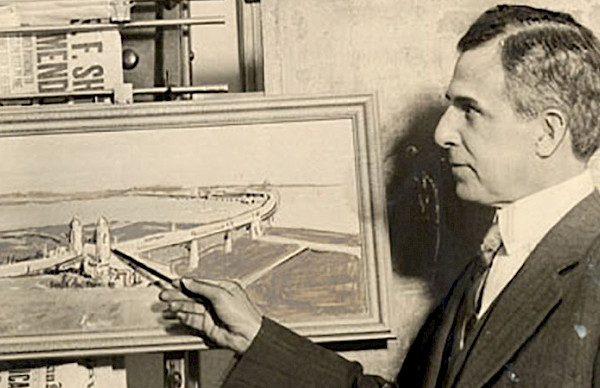

Known as the “father” of the Jacques Cartier Bridge, engineer Philip Louis Pratley spent from 1925 to 1930 designing the plans for this structure that is now regarded as a symbol of Montreal. Pratley earned an enviable reputation in engineering thanks to his innovative mathematical approach to structural design and analysis.

Did you know that when the Jacques Cartier Bridge was built, it was one of the longest cantilever bridges in the world?

Born in Liverpool, England, Pratley earned an honour’s degree in civil engineering structures and received the William Rathbone Medal given to the best students in engineering.

After immigrating to Canada, he got a job in 1906 as a designer-draftsman at the Dominion Bridge Company in Montreal. He worked for this well-regarded firm until 1920. In 1909, at the age of just 25, he was given an important role in the design of the Quebec Bridge to replace the one that had tragically collapsed two years earlier. When it opened in 1917, this bridge was the longest in the world!

In 1921, Pratley started a private consulting firm and partnered with Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Nicholas Monsarrat to form the Montreal civil engineering firm Monsarrat & Pratley. This firm oversaw the construction of the Jacques Cartier Bridge and other major structures in Canada and the United States.

The Jacques Cartier Bridge is the first bridge that these business partners worked on together. Pratley was responsible for the full design of the structure spanning over 1.6 km. After its construction between 1925 and 1930, the Jacques Cartier Bridge was the fifth longest cantilever bridge in the world. With five lanes, it was also recognized in 1937 as the most modern wide bridge of its category.

Since 1987, the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering has awarded the P.L. Pratley Award to the engineer who has written the best technical paper on bridge engineering.

Pierre-Étienne Flandin studied in France at the Lycée Carnot, where he received his degree in political science and law before being called to the bar in Paris. A politician with a true passion for transportation, he was the Minister of Public Works in France when the Harbour Bridge was renamed the Jacques Cartier Bridge. He was therefore a member of the French delegation that attended the bridge’s official naming ceremony.

What was Pierre-Étienne Flandin’s mark on history?

From the start of his career, Pierre-Étienne Flandin fell in love with aviation. He received his pilot’s license while fulfilling his military service and fought with the AF33 French air force squadron in World War I during the Battle of the Yser. He was then summoned to serve as aeronautics rapporteur for the Senate Army Commission and oversaw the commission before becoming its president. As the years went on, he helped develop commercial aviation in France, as he was responsible for passing the country’s first air transportation budget. His other contributions include overseeing regulations surrounding air traffic, in addition to helping develop training centres for reserve pilots. Flandin became one of the most eminent air industry specialists of his time.

For the official name change of the Jacques Cartier Bridge, Flandin attended the official ceremony, where he had a front-row seat to see the French Government give Canada a bronze bust of the famous Malouin explorer and discoverer.

Source: BAnQ

Photo credit : Bibliothèque nationale de France

“Three times the charm” is a saying that applies to the history of the Jacques Cartier Bridge, as two projects for a bridge to relieve increased car traffic between Montreal and the South Shore were abandoned due to a lack of government support . However, a third project was accepted in 1924 after the Harbour Commissioners of Montreal finally persuaded the government to finance the bridge.

Consulting engineers Charles Nicholas Monsarrat , Philip Louis Pratley and their associate, Joseph Baermann Strauss, partnered for this project, and together they chose the location of the future bridge, prepared the plans and drafted the estimâtes.

Who were these men who designed the Jacques Cartier Bridge?

Charles Nicholas Monsarrat (1871-1940) was a Canadian bridge designer. After graduating from private school in Montreal, Monsarrat worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway and became its chief engineer of bridges in 1903. In 1921, he founded a firm with Philip Louis Pratley, and they worked as consulting, design and supervising engineers. Monsarrat was responsible for the design and for overseeing the construction site of the Jacques Cartier Bridge.

Philip Louis Pratley (1884-1958) was a consulting engineer who was born in Germany. After immigrating to Montreal in 1906, he worked on the design and construction of many long-span bridges.

Joseph Baermann Strauss (1870-1938) was an American engineer of German descent who was the chief engineer of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, one of the seven wonders of the modern world. A prolific engineer, he helped build 400 drawbridges in the United States. His dream was to build “the biggest thing of its kind that a man could build.”

Founded in the middle of the 19th century, the Dominion Bridge Company built all of Canadian Pacific’s rail bridges between Montreal and Vancouver. Over the years, this major company honed its steel expertise by working on many major structures, such as the Quebec Bridge, the Champlain Bridge, the structure of the Château Frontenac, the Mount Royal Cross and, of course, the Jacques Cartier Bridge!

How was the Dominion Bridge Company involved in the construction of the Jacques Cartier Bridge?

The $7-million contract that the Dominion Bridge Company won for the Jacques Cartier Bridge’s superstructure was the biggest construction contract ever awarded in its history. Two other companies—Dufresne Construction along with Quinlan, Robertson and Janin—divided the $1.1-million contract for the quays and approaches. The Dominion Bridge Company also built the Jacques Cartier Bridge’s main steel structure, which stands 590.5 meters tall over a span of 2,725 meters.

Where were all the women?

As was the case for many Canadian companies during the First World War, the Dominion Bridge Company hired women while men were away on the battle field. The company had to temporarily change its production for the military’s munitions needs, and many women employees helped manufacture shells at the factory.